How to analyze SSB Melee with Python

Super Smash Bros. Melee (Melee from here on) is a Nintendo party game for the Gamecube where you and your friends try to knock each other off the stage as a variety of Nintendo and third party characters. You might remember it from an early 2000s play date where your best friend would relentlessly transform into a block and drop on top of you as Kirby. Or maybe you remember it as that game the nerds down the hall in your dorm would play late into the night as you tried to sleep on a Wednesday (for the record, I was one of the nerds, not one of the people trying to sleep). Regardless, despite being nearly 20 years old, it has a thriving competitive scene that can draw tens of thousands of viewers. I started following the competitive Melee scene 5-6 years ago, and since then it has only continued to grow. When I started doing projects to transition into data science, I knew I wanted to do something with all the data and tools the community has put together. My next few blog posts will cover my exploration of competitive Melee with data science tools. For this post I’ll just focus on how you can get games into a format where you can do further analysis.

Getting Melee games into Python

You might ask yourself how we could possibly explore a Gamecube game with modern tools. As with most things related to Melee, the answer lies with its fans. Over the years, a number of developers have dome some magical things with Melee. The one that is most important here is Project Slippi. Slippi allows for the recording of games into .slp replay files, which can then be viewed with an emulator. As a sidenote, Slippi also allows for online matchmaking with rollback netcode (which to me is basically magic) on a game that came out for a console that could not connect to the internet. It’s absolutely incredible. Even better, there are libraries that let you parse through the Slippi replay files in several languages, some written by the Slippi developers, some written by community members. I’ll be using the py-slippi library to parse through games with Python.

Using py-slippi to read in games

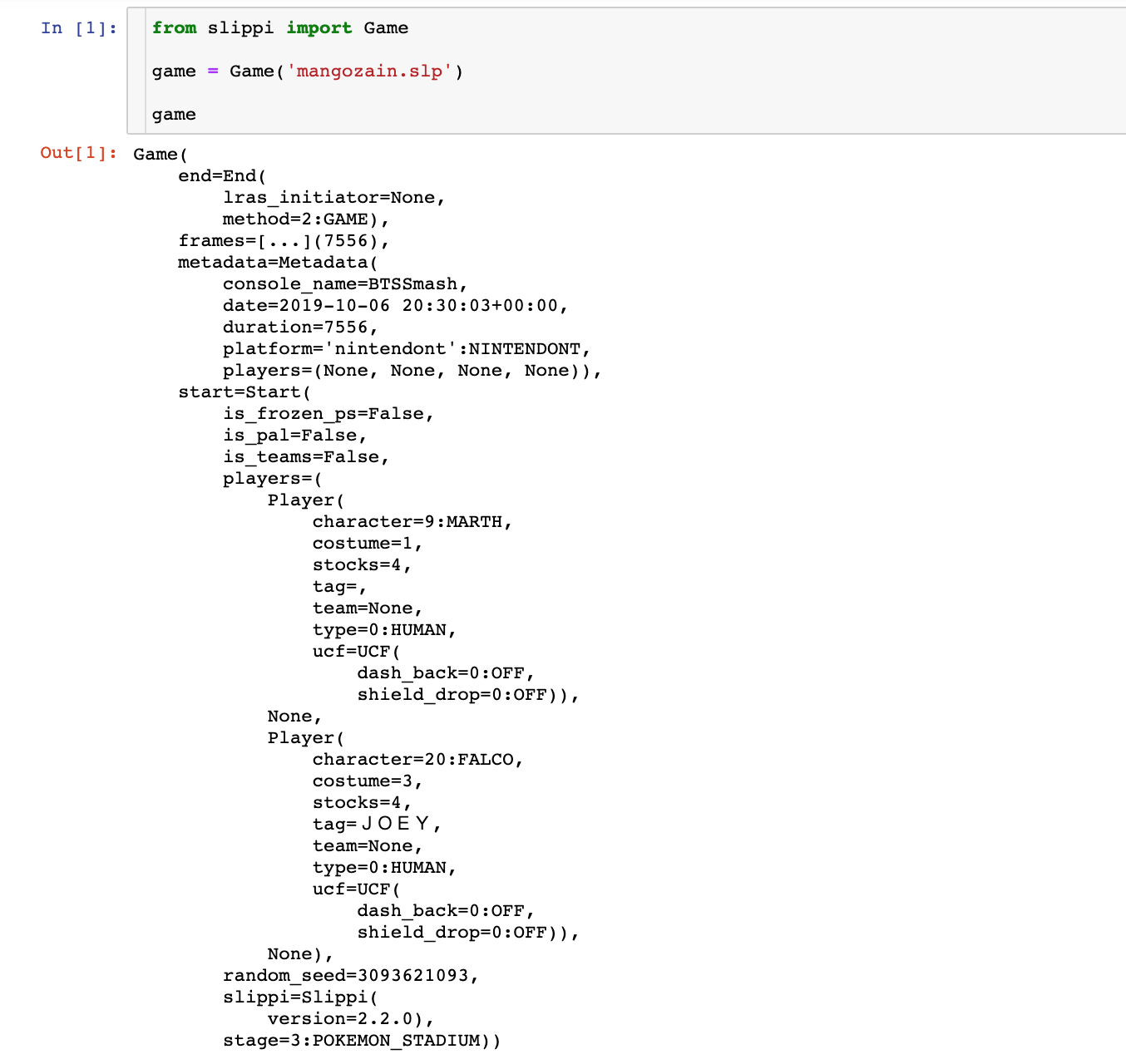

py-slippi supports both reading in a saved .slp file as well and reading in a stream (a file being written while it’s being played). I’ll focus on the former as it is more straightforward as well as what I did for my project. In order to read in a game, just treat it as you would any other file and pass it into a py-slippi Game object. This Game is the primary object we’ll be using, and it contains all the data in the game saved to the .slp file. If we just print out this object, we can see its general structure:

Essentially, the Game we put our replay file into stores all the game data into a bunch of enum-like objects. In order to access the stage, for example, we’d simply use game.start.stage. If we just want the name of the stage, use game.start.stage.name. You can see all the general metadata of the game that py-slippi provides in the picture above, and they are all accessed in a similar way. One thing to note that occurs throught the Game object is that even if there are only two players, the Game object has info for all four ports (note the two Nones in the players field under start). I found it is best to keep track of which ports are occupied as these will stay consistent throughout the game.

Accessing frame-by-frame data

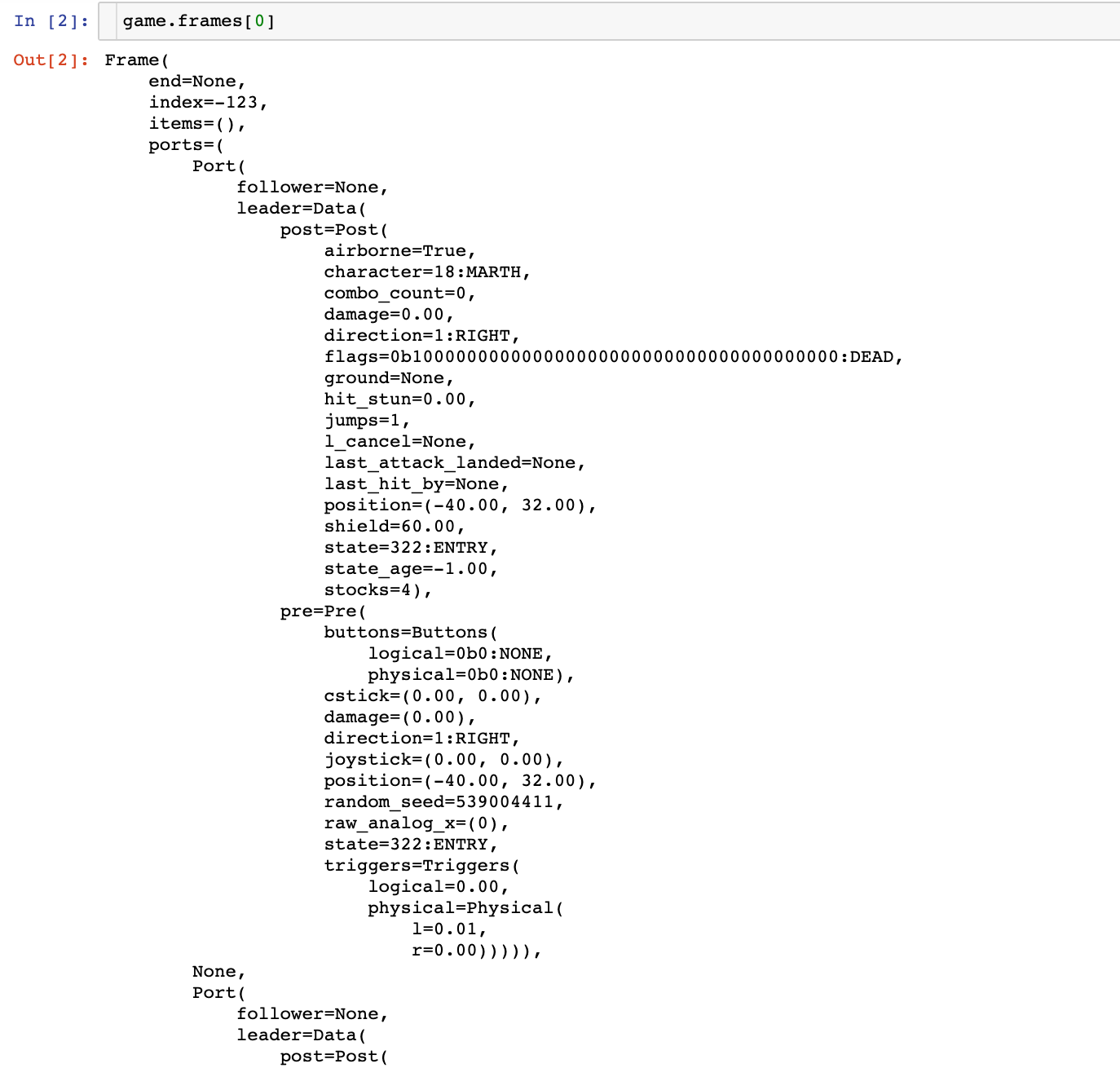

Now that we’ve seen how the game metadata is stored, we can start looking at the frame by frame data. A frame occurs every 1/60th of a second in Melee and is essentially the smallest unit of time where the gamestate is evaluated and updated. All the frames that make up a game are stored sequentially in the frames attribute of a Game object, whose output is suppressed in the picture above. We simply access frames like a list. For example if we look at the first frame of our example game we get:

As you can see there’s quite a bit of data here. I don’t want to go through everything but I do want to talk about the general structure because it can be a bit unclear when you are just getting started. The important thing to know is that the data you most likely care about is in ports. ports will always have 4 entries, but only the ports filled by players will be filled. For the non-None entries, each port has two fields: leader and follower. This is only relevant for the Ice Climbers, a character that actually consists of a main character and a follower character, controlled by the computer if being played by a human. For all other characters only the leader field will be filled with data. The leader field has two subfields: pre and post. These refer to the information of that character at the beginning and end of the frame in question. The pre field mostly consists of information about controller inputs, while the post field contains more in-game information, such as the action-state of the character in question and their stock (life) count. post is what I used most in my game analysis, because I think it contains the most interesting information about what is actually happening in the game.

Conclusion

I hope that this is useful for anyone who wants to get started analyzing Melee games with Python. In the my next few blog posts I’ll go more in depth with what I did for my final project for Metis, where I calculated in game win probabilities. If you’d like to jump ahead and see what I did, you can find that project here.