Calculating game statistics in SSB Melee with Python

This is the second in my series of blog posts on analyzing Super Smash Bros. Melee with Python, which I did for my final project at Metis. For the first blog post, on how to use the py-slippi package to import .slp replay files into python, you can go here. You can also find the full project on Github here

Introduction

While the previous blog post was meant to be more of a standalone introduction to using Python to analyze Melee games, starting with this post I want to get more into the particulars of my project. My ultimate goal for my project was to train a machine learning model to predict the in-game win probabilities at any time given the state of a Melee game. I’ll go more into my motivations for this more in the next blog post, where I’ll talk about my modeling approach, but for now I want to focus on how I got individual Melee games into a format where they could be used as data for a model. The way I decided to do this for my project was to break up a game into time slices (I eventually decided on every 5 seconds), find in-game information at those time slices, then put all that information, along with general information about the game that did not change with time, into a Pandas dataframe. This post will go over how I did both.

Finding general (time-independent) game data

While I wanted to focus on in-game statistics, such as stocks, damage, number of hits, etc., I also believed going into the project that certain time-independent game properties would affect the odds of which player would ultimately win. The time-independent properties I decided to use were simple: the two characters the players were playing as and the stage they were playing on. I also wanted to include these because I was hoping the model would be able to use these properties to make predictions when it had little other information to go off of, such as at the beginning of the game. I had hoped, for example, that the model would pick up on the fact that Marth has a large advantage versus Fox on the stage Final Destination, and so would give the Marth a high chance of winning at the beginning of the game. The other time-independent property I wanted was the winner of the game, which I used as my objective feature while training my model.

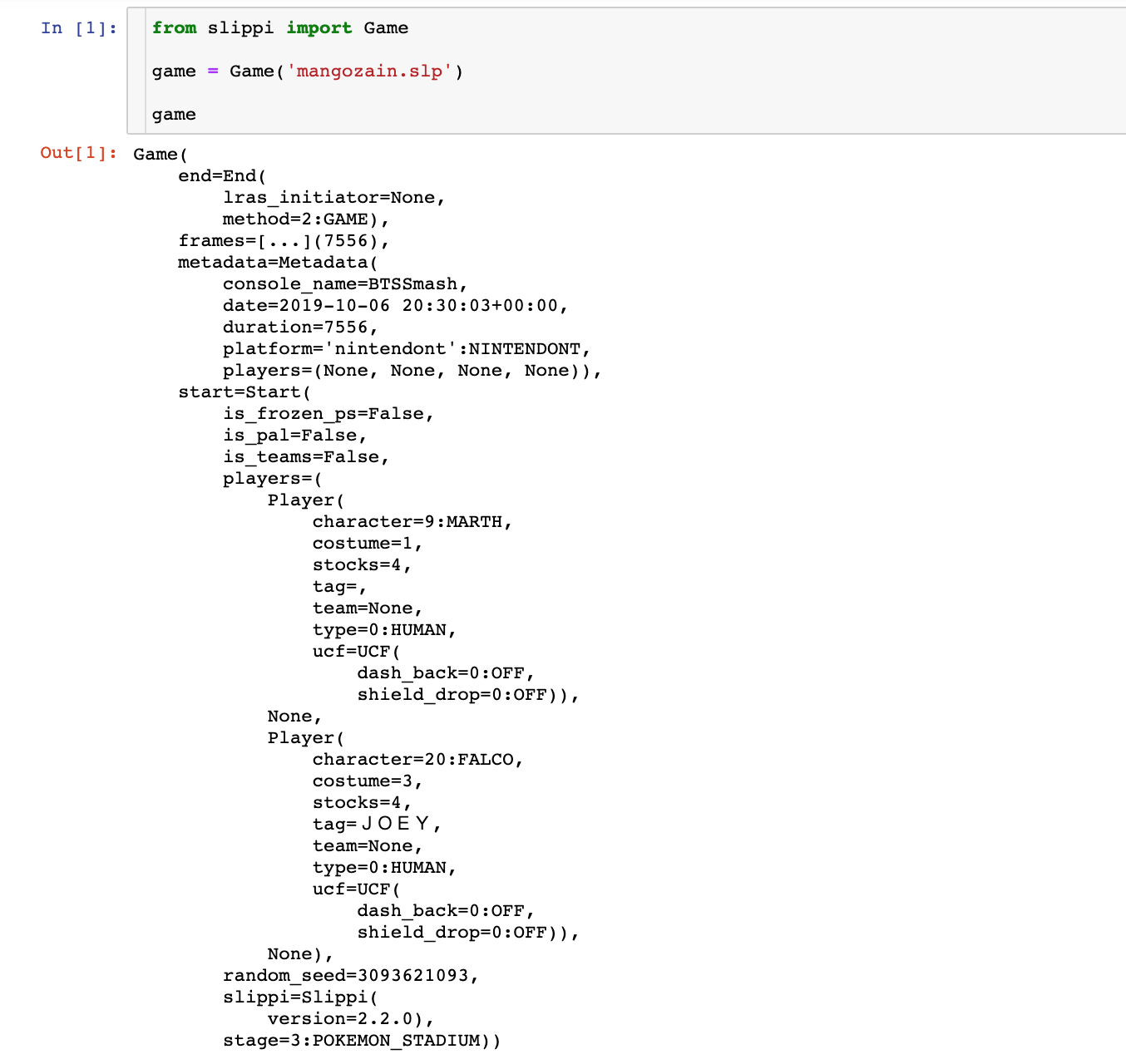

As discussed in my previous post, this kind of information is available in the form of enums in the py-slippi Game object. However, there are some nuances that I wanted to go over here. Before showing any code however, recall the structure of a Game object looks like this:

Stage

The stage of the game is straightforward to access; simply use game.start.stage.name

Characters

The difficulty with finding which characters players are playing as is that the ports the players are occupying varies between games. Gamecubes have four possible ports players can plug their controllers in to, so in games with two players (the focus of competitive Melee and my project), there are several different possible port configurations. In py-slippi, the fields relating to player data will always have four entries, on for each port, but any unoccupied ports will just have None instead of actual information. This port-dependence comes up several times, so I decided to make a function to find the occupied ports.

def get_ports(game):

"""

Returns tuple of ports occupied by players in Slippi Game

Args:

game: PySlippi Game

"""

player_tup = game.start.players

ports = tuple([i for i in range(4) if player_tup[i] is not None])

return portsNow that we have a way to get the ports, we can access the character names for each player:

def get_characters(game, port1, port2):

"""

Returns tuple of characters (Fox, Falco, etc.) being played by players in occupied ports

Args:

game: PySlippi Game

port1 (int): First occupied port

port2 (int): Second occupied port

"""

player_tup = game.start.players

chars = (player_tup[port1].character.name,player_tup[port2].character.name )

return charsWinner

The winner of teh game is not actually one of the fields you can simply access. In order to find the winner of a game we have to figure out who had more stocks at the end of the game (i.e. the last frame), with a few exceptions. First, if someone quit out of the game, then the person who did so lost. This is stored in the lras_initiator field, which gives the port of the player who quit out, or None otherwise. Next, if the players had the same number of stocks (due to running out of time), then the player with lower damage is the winner. Besides these two cases however, we just need to find the number of stocks each player and compare them. To access the last frame, we just need to look at the last entry in the frames list, i.e. frames[-1]. The code for finding the winner of a game is:

def get_winner(game, port1, port2):

"""

Returns 1 if player with lower port is winner

Args:

game: PySlippi Game

port1 (int): First occupied port

port2 (int): Second occupied port

"""

lras = game.end.lras_initiator

if lras is not None:

if lras == port1:

return 0

else:

return 1

p1_stocks = game.frames[-1].ports[port1].leader.post.stocks

p2_stocks = game.frames[-1].ports[port2].leader.post.stocks

if p1_stocks == p2_stocks:

p1_damage = game.frames[-1].ports[port1].leader.post.damage

p2_damage = game.frames[-1].ports[port2].leader.post.damage

return p1_damage > p2_damage

return int(p1_stocks > p2_stocks)For this particular project, I decided to return 1 if the player with the lower port won, and 0 if they lost, though of course this could be changed

Calculating in-game statistics

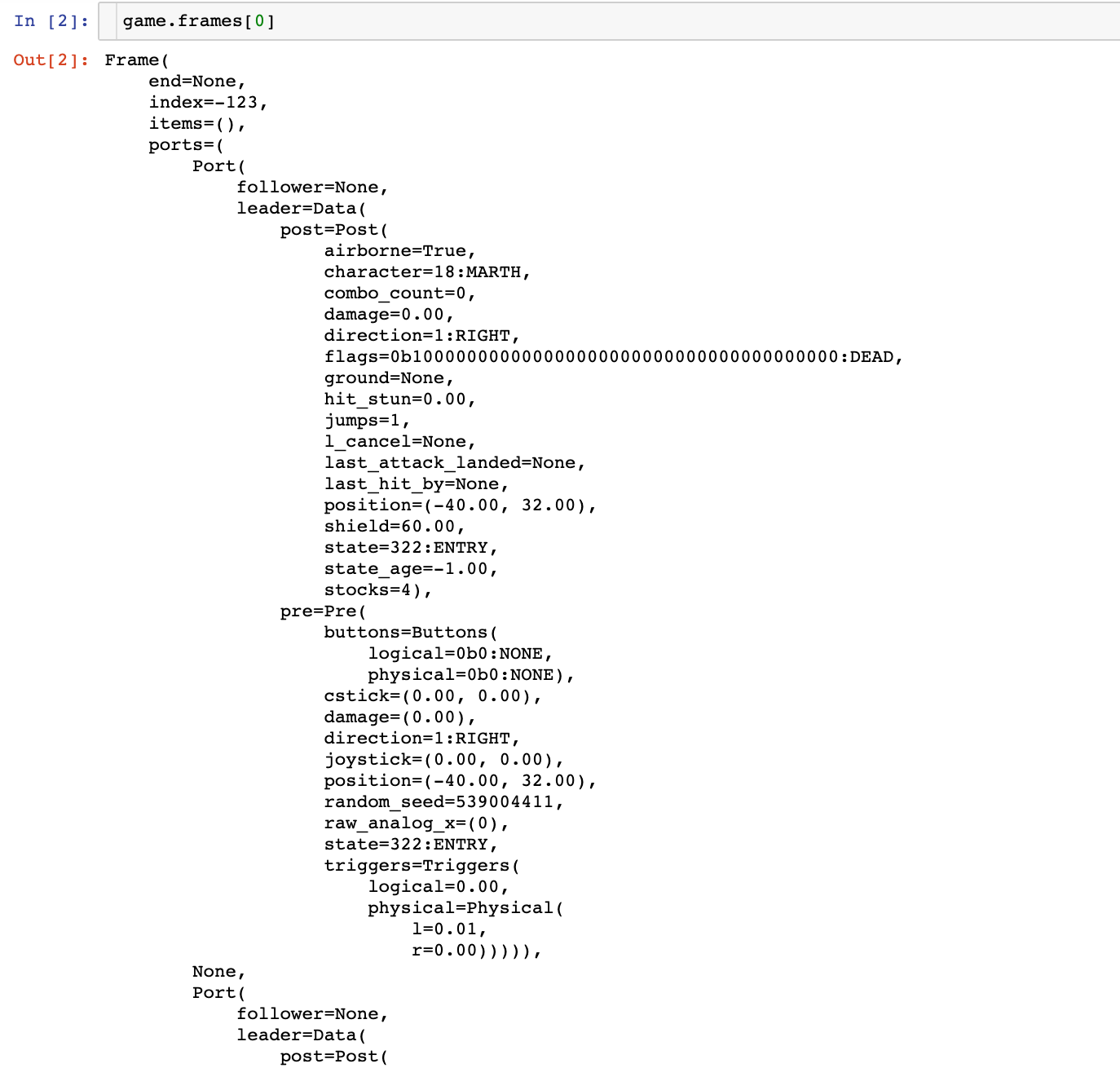

Now that I’ve showed how to get soem of the more basic information on a game, I’ll talk about getting the information that changes with time. As you might guess, all this information is contained in the frames field of the Game object. As a reminder, this is the information that we have for each frame:

Note the None in ports: this means the second port isn’t occupied while the first and third are (the third port information is just cut off).

A large amount of information can be calculated from this information. The statistics I ended up focusing on are stocks, damage, number of hits (of different types) landed, number of defensive actions, and information related to when stocks were lost by each player. This is just scratching the surface though - the main Slippi developers have made code to count things like wavedashes or neutral opening, but they do so in Javascript. I’ll go through my logic for calculating each of these, but to see my full code see the file data_utils.py in the utils folder in the project repo.

General notes

Before diving into my logic for calculating statistics, I wanted to go over some things about the frames. First, a frame is a 60th of a second, so if you want to access information every 5 seconds (for example), you would need to check every 300 frames. Second, the most important field for most of these calculations is the state field. Characters can be in a large number of states, so see the documentation for all of them.

Stocks and damage

Stocks and damage for each character are the simplest things to access since their information is contained in each frame. The code to get stocks and damage for list of times is:

for i, frame_num in enumerate(times):

p1_stocks[i] = game.frames[frame_num].ports[port1].leader.post.stocks

p2_stocks[i] = game.frames[frame_num].ports[port2].leader.post.stocks

p1_damage[i] = game.frames[frame_num].ports[port1].leader.post.damage

p2_damage[i] = game.frames[frame_num].ports[port2].leader.post.damageNumber of hits

To calculate how many hits of each type (grounded hits, aerials, and smashes), we need to check if a characters damage has increased from the previous frame. If it has, then we look at what state the other player is in, which determines what type of attack they landed

p1_prev = game.frames[frame_num-1].ports[port1].leader.post

p2_prev = game.frames[frame_num-1].ports[port2].leader.post

#If a players damage value has changed, update the other players hits

if p2_cur.damage > p2_prev.damage:

p1_hits_landed +=1

if p1_state in GROUND_ATTACK_STATES: p1_ground_attacks += 1

elif p1_state in SMASH_ATTACK_STATES: p1_smashes += 1

elif p1_state in AERIAL_ATTACK_STATES: p1_aerials +=1

if p1_cur.damage > p1_prev.damage:

p2_hits_landed +=1

if p2_state in GROUND_ATTACK_STATES: p2_ground_attacks += 1

elif p2_state in SMASH_ATTACK_STATES: p2_smashes += 1

elif p2_state in AERIAL_ATTACK_STATES: p2_aerials +=1In this code ..._ATTACK_STATES is just a list of numbers containing all the action state numbers that correspond to those type of attacks. I’m also keeping track of the total number of hits.

Grabs

Grabs are a bit different than other attacks because grabs themselves don’t do damage. We could check the number of throws, or just check to see when the players enter into certain states that represent a successful grab. I chose to do the latter. The code to check if a player entered a certain state is relatively simple:

def entered_state(p_cur, p_prev, state_list):

"""

Returns true if player entered state in state_list in the current frame

Args:

p_cur: post object for current frame, ie game. ... .leader.post

p_prev: post object for previous frame, ie game. ... .leader.post

state_list: List of ints representing action states

"""

cur_state = p_cur.state.value

prev_state = p_prev.state.value

return cur_state in state_list and prev_state not in state_listAnd to calculate the number of successful grabs the code is just

if entered_state(p1_cur, p1_prev, GRAB_STATES): p1_grabs+=1

if entered_state(p2_cur, p2_prev, GRAB_STATES): p2_grabs+=1Defensive actions

I also wanted to include defensive actions, such as the number of frames sheilding up until that point in time and the number of rolls. These just check the current state and if the correct state was entered, respectively:

#Shielding states

if p1_state in SHIELD_STATES: p1_frames_shielding+=1

if p2_state in SHIELD_STATES: p2_frames_shielding+=1

#Roll states

if entered_state(p1_cur, p1_prev, ROLL_STATES): p1_rolls+=1

if entered_state(p2_cur, p2_prev, ROLL_STATES): p2_rolls+=1Other stock information

Finally, I also wanted to track how many stocks each player lost early, which I defined somewhat arbitrarily as 50%, and how long it had been since they last lost a stock. The logic for this is just as it sounds: if a player’s stock value changed, check if they were at 50% or lower and reset a counter, and if not just increment that counter. This counter, and all the other information I’ve discussed was collected into lists at set time intervals before putting it all into a dataframe.

#If a player has lost a stock, check if they lost it under 50%, and reset the timer for time since they

#lost a stock

if p1_cur.stocks < p1_prev.stocks:

p1_time_since_stock = 0

if p1_prev.damage <=50:

p1_stocks_before_50 +=1

else: p1_time_since_stock +=1

if p2_cur.stocks < p2_prev.stocks:

p2_time_since_stock = 0

if p2_prev.damage <=50:

p2_stocks_before_50 +=1

else: p2_time_since_stock +=1Conclusion

These is all the information I collected directly from games in order to make a model. As I said, there’s a lot of room for more advanced statistics, though this information worked fairly well with some further feature engineering. I hope this has helped anyone who wants to do a similar project, and again if you’t like to see the full repo you can find ithere.